HELLAH HORRAH : The Monkey, What Follows Us Out of the Underworld

Hey there horror hawtnesses! Hellah Horrah’s back honey’s like Persephone , dragging winter up by the spine, dirt still under my nails and teeth, pomegranate juice on my tongue leaves a taste so bitter sweet, counting the seasons by what I’ve survived.

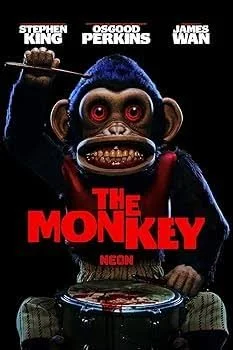

Today’s descent: The Monkey.

Let’s start where the blood starts … the twin performance. Because whew. Watching one man peel off his humanity like wet wallpaper and step into something feral? Delicious. He doesn’t just act like two people. He rots into two people. One holds onto the last threads of warmth, the other grows talons where empathy used to live. You watch the jaw tighten, the eyes hollow, the posture shift from man to predator. That kind of transformation is sacred horror. That’s altar-level commitment.

And yeah the loss of the charm? The shedding of the “pretty”? Necessary. Because real horror isn’t polished. It’s raw nerve and bad decisions and the moment you realize the monster didn’t arrive… it grew.

The beautiful constant, competent, desirable, victorious.

The kind of man cinema usually protects.

The Monkey takes that protection away.

Playing twins, he performs a deliberate unmaking. One brother clings to the surface world of order, restraint, the illusion of control. The other embraces the underworld logic: appetite, obsession, talons sharpened by permission. You can see the exact moment he stops trying to be admired and starts trying to be true. That’s not loss of sex appeal, that’s descent. That’s an actor choosing Hades over Olympus.

And the collision between the brothers?

It’s not spectacle.

It’s inevitability.

Sibling rivalry here isn’t petty or jealous, it’s epic. Iliad-level. Two men born of the same house, carrying the same inheritance, doomed to reenact the same war with different armor. Watching them share space feels like watching Achilles and Hector circle each other not because one is good and one is evil, but because fate demands blood before clarity.

Every scene between them crackles with the knowledge that only one version of the self can survive the return. Every scene between them feels like standing too close to a gas leak with a lighter in your hand. You know it’s coming. You can smell it. And when it hits? It’s messy and loud and unfair, exactly how family wounds behave.

And then there is the father.

The quiet casualty.

Like Priam standing at the gates, forced to witness the consequences of lineage. You feel his sorrow not as guilt, but as grief, the kind that comes from loving fully and still failing to prevent disaster. Horror rarely honors elders this way, but here it does. His pain isn’t loud. It’s devotional. It’s the grief of a man realizing the gods do not bargain.

Now.

The Monkey.

This isn’t an object.

It’s an emissary.

A threshold guardian. A small, grinning Charon ferrying anyone who touches it across a river they didn’t mean to cross. Once you’ve held it, you’re marked. The film understands what myth has always known: curses don’t chase you. They wait for you to accept them.

Everyone who comes into contact with the monkey enters the cycle of desire, denial, consequence. No exemptions. No heroes. Just passage.

So what tarot card lives here?

This is The Devil, unquestionably but not as a demon.

This is the Devil as Hades himself.

Not cruel.

Not chaotic.

Simply inescapable.

The chains are psychological. The captivity is consensual. The twins are bound not by the monkey, but by what it awakens. One believes the underworld is home. The other believes he can visit and leave unchanged. Myth tells us how that ends.

And aligning this work with tarot means you don’t depict the curse.

You depict the crossing.

The moment Persephone tastes the fruit.

The second Odysseus lingers too long with Circe.

The pause before Achilles chooses glory over life.

Visually and conceptually:

The tension between brothers as mirrored selves

Hands reaching, recoiling, already stained

The father as witness, not savior

Space that feels seasonal — half light, half shadow

The sense that return is possible, but never complete

Final Hellah truth:

This film understands that horror is not about monsters —

it’s about what we bring back with us.

Once you’ve touched the underworld, something always follows.

— Hellah 🖤